Chapter 1: Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap

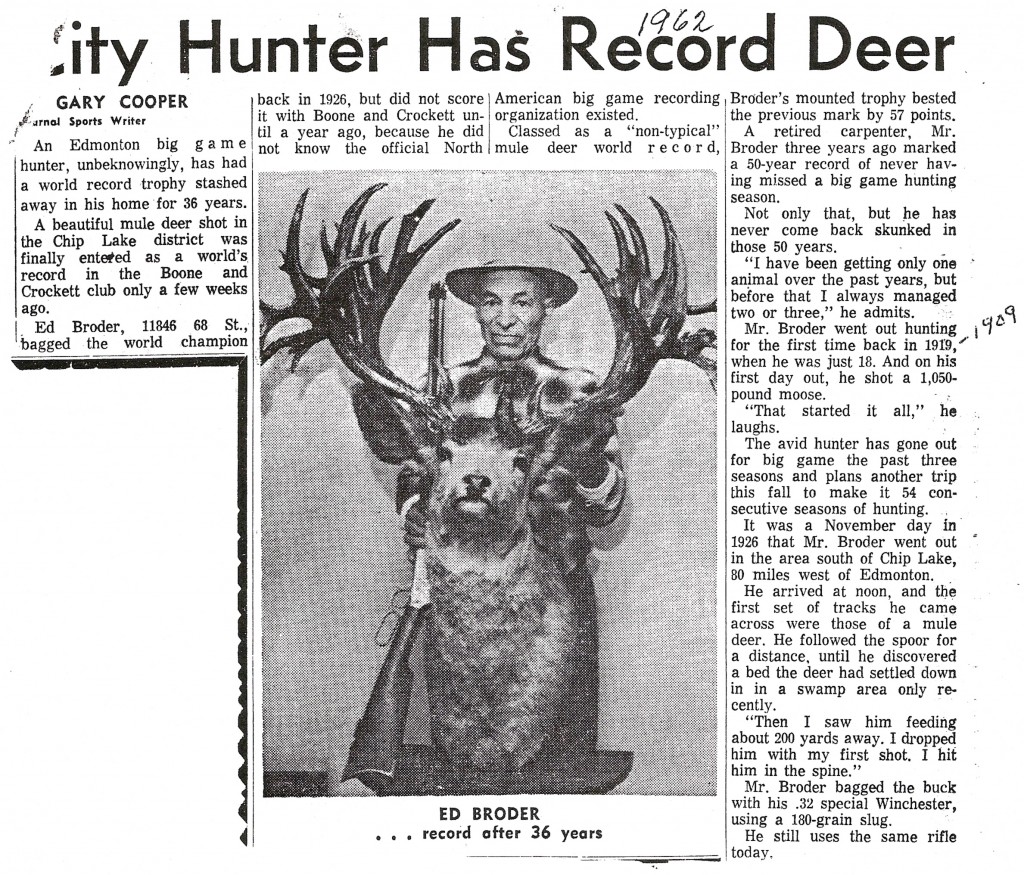

What is the World Record “Broder Buck”? The legendary Broder Buck is the world-record non‑typical mule deer officially scored by the Boone & Crockett Club.

- Hunter: Ed (Edmund) Broder

- Location: Near Chip Lake, Alberta, Canada

- Date taken: November 1926

- Final Boone & Crockett score: 355 2/8 inches — the highest non‑typical mule deer ever recorded

The rack surpassed the previous record by over half as many points and remains unmatched more than 90 years later. It represents the largest non‑typical mule deer in North American record books—and still holds that status today.

Its story is dramatic: Ed Broder didn’t leave a will. After his death in 1968, a dispute among heirs led to a decades-long legal battle that exposed Canada’s Department of Justice as a swamp full of white collar criminals—Justices of the Court and Lawyers—that willfully acted in a conspiracy to frame and jail Donald Broder at Edmonton Remand Center until he succumbed to their demands to extort The Broder Buck.

But don’t take my word for it. The court documents will speak for themselves.

When Ed Broder passed (December 26, 1968), Donald Broder’s siblings took it upon themselves to help themselves to his personal belongings—despite no formal probate process being filed. They took the more valuable items, including Ed’s Model T, firearms, tools, saddles, and collectibles. Richard Broder claimed the family home.

In 1970, Donald Broder went to that same home and claimed the Broder Buck, maintaining exclusive possession of it for over 25 years. Then, in 1997, after Donald and his son Craig displayed the Broder Buck at the Edmonton Sportsman Show, Craig was served with a demand letter from George Broder.

Lawyers at the time made it clear: none of the siblings had any legal right to demand its return without first going through probate and being appointed by the court. No such application had ever been made in over 25 years. The limitation period had long expired—unless the siblings could prove Donald had agreed to hold the Buck on behalf of them all, and account for what they themselves had already taken.

Donald Broder retained lawyer Joseph Kueber of Bryan & Company, who filed a Statement of Defence arguing that the plaintiffs had no standing—no legal or equitable right to claim The Broder Buck. Back in 1969–1970, Donald’s siblings had already taken what they wanted from their father Edmund Broder’s belongings without any formal process.

Now, if they wanted to make claims, they first had to apply for probate, appoint a Personal Representative, and follow Surrogate Court rules to formally demand the return of all personal effects—not just The Broder Buck. Donald Broder rightly pointed out that 27 years had passed and the limitation period had likely expired, but he was still willing to cooperate if probate was properly granted and an accounting of everything taken could be made.

In October 2000—over three years after the original Statement of Claim was filed—plaintiffs’ lawyer Elizabeth MacInnis of Weir Bowen requested consent from Donald and Craig Broder’s lawyer to file the Certificate of Readiness and close pleadings in Court Action #9703-12949. Donald Broder refused, because no probate had ever been applied for. Without probate and a properly appointed Personal Representative, the plaintiffs had no legal standing to sue on behalf of Edmund Broder’s estate. If MacInnis closed the pleadings before fixing that, Donald could apply to have the whole matter struck.

Even if a Personal Representative had been appointed, the two-year limitation to add or substitute a party had already expired in July 1999. Still, MacInnis sought and obtained a court order allowing her to file the Certificate of Readiness by March 15, 2001, and Donald Broder was ordered to pay $1,000 in costs for not consenting. But she never filed the Certificate as ordered. Instead, on May 24, 2001 (well past the deadline) she suddenly applied for probate and falsely claimed Donald had been served. She then succeeded in appointing two of her own clients as Personal Representatives, creating a clear conflict of interest.

MacInnis should never have been allowed to represent the estate while acting against a beneficiary, Donald Broder, in the same legal action she herself had just closed. Siblings cannot sue each other over estate property until probate is granted and a Court-appointed Personal Representative is in place to act properly on behalf of the deceased.

Donald Broder and Craig Broder had already won the lawsuit—legally and procedurally—because:

- Elizabeth MacInnis forced the pleadings closed on herself by court order before ever applying for probate or appointing Personal Representatives through the Surrogate Court. That means the plaintiffs locked themselves out of the ability to sue properly, because no one had the legal authority to act on behalf of Edmund Broder’s estate at the time pleadings were closed.

- The 2-year limitation period had already expired. The original Statement of Claim was filed July 8, 1997. By July 9, 1999, the time limit to add or substitute parties—like legally appointed Personal Representatives—was over. By December 18, 2000, when they tried to move things forward, it was far too late.

Knowing this, Donald and Craig Broder had their lawyer, Robert Sawers, file for a jury trial—but only to secure the procedural win. They didn’t even need a jury, because the plaintiffs had no standing left. Just before the jury application, Sawers filed a Rule 129 Application, arguing the entire lawsuit was frivolous, vexatious, and an abuse of court process—because the plaintiffs, in their personal capacities, had no legal right to sue. Only properly appointed Personal Representatives could do that.

Supporting this was a precedent-setting case: Mugford v. Mugford, from the Newfoundland Court of Appeal. The case made it clear: only an estate administrator or Personal Representative has standing to bring legal action on behalf of someone who has passed away. In the Mugford case, the court ruled the claim invalid because the person suing had no legal right to do so—just like in the Broder case.

Quote from the ruling:

“It is the role of the administrator and not the role of [a sibling] to put this to the test… The action was wrongly conceived… and ought not to have proceeded.”

In short: Donald and Craig Broder had already won, because the lawsuit against them was fatally flawed from the start.